Adevăruri nefiltrate, sau când viața de tenismen nu e așa cum ți-ai închipuit-o

Radu Marina | 6 martie 2019Ca noi toți, tenismenii suferă, se confruntă cu obstacole complicate, au probleme, au temeri, n-au garanții. Pică în depresii, au conturile goale, au probleme în familie, se confruntă cu sentimentul că nu sunt acceptați. Sunt oameni.

Din exterior, viața tenismenilor pare fără griji. Călătoresc mult, participă la turnee cu premii de milioane de dolari, sunt cazați la cele mai luxoase hoteluri, au parte de tot ce își doresc, par fericiți. De astea se bucură însă doar unii, care au făcut sacrificii enorme pentru a ajunge la cel mai ridicat nivel. Alții sunt într-o permanentă luptă de supraviețuire. Iar cei mai mulți nu vor ajunge acolo niciodată.

Experimentul făcut de Noah Rubin, un jucător american de tenis, câștigător la Wimbledon juniori (2014) și jucător de Top 125 în circuitul ATP, ne dă o altă perspectivă asupra a ceea înseamnă să fii jucător profesionist de tenis. E, de fapt, un exercițiu util pentru toți fanii tenisului (și nu numai) – care ne arată că, de fapt, tenismenii suferă, se confruntă cu obstacole complicate, au probleme, au temeri, n-au garanții. Pică în depresii, au probleme în familie, se confruntă cu sentimentul că nu sunt acceptați. Sunt oameni.

„Oamenii nu înțeleg ce înseamnă să fii numărul 100 mondial. Ei cred că mergem cu avioane private, stăm la Ritz Carlton tot timpul și jucăm în fața a peste 15.000 de oameni. Există și persoane, clasate între locurile 100 – 200, care au făcut asta, dar sunt puțini. În cea mai mare parte jucăm în tot soiul de cluburi fără arbitri de linie, fără copii de mingi. Asta e adevărat provocare”, mărturisea Rubin într-un interviu pentru USTA.

Rubin a creat @behindtheracquet, un cont de Instagram care găzduiește perspectiva nefiltrată a jucătorilor. Noah folosește în mod constructiv accesul de care beneficiază și ia un rol de creator de conținut, ajutându-se pentru asta de colegii și colegele sale din vestiar, pe care, la rându-i, îi ajută să prezinte ce se află în spatele rachetei, ce nu vedem noi de la televizor. Proiectul „Behind the Racquet” oferă fanilor o perspectivă nuanțată și le dă oportunitatea de a înțelege mai multe despre persoană, nu doar despre jucătorul de tenis.

Apărut într-un moment în care sunt în toi discuțiile din lumea tenisului în ce privește schimbările implementate de ITF în tenisul de nivel secundar, „Behind the Racquet” a prins rapid contur; sunt deja peste 15 jucători care au acceptat această provocare, printre care Madison Keys, Tennys Sandgren, Sachia Vickery, Dustin Brown, Nicole Gibbs, Bjorn Fratangelo.

Iată câteva dintre pasaje din povești, dar vă recomandăm să le citiți pe toate:

Sachia Vickery, jucătoare de top 100 în circuitul WTA:

„Am avut de străbătut o cale foarte dificilă pentru a ajunge unde sunt astăzi. Mama mea a emigrat aici (n.a. în Statele Unite) din Guyana, în 1987, în căutarea unei vieți mai bune. Până am mai crescut, mama a lucrat în trei locuri doar pentru a putea să mă trimită pe mine la turnee. În ciuda acestor lucruri, ea a găsit întotdeauna o cale pentru ca eu să pot continua cu tenisul. Mi-a fost greu să călătoresc singură, dar asta era singura opțiune. Trebuia să câștig meciuri astfel încât să-mi pot permite să merg și la alte turnee. Mi s-a repetat că sunt prea mică de înălțime ori că jocul meu nu mă va ajuta să fiu în top 100.

Am fost pe punctul de a renunța, chiar înainte de a câștiga naționalele U18, în 2013, la simplu și dublu. Acele turnee m-au ajutat să intru pe tabloul principal la US Open cu ajutorul unui wild card, la simplu și dublu. Înainte de aceste campionate naționale, nu aveam nici măcar bani să-mi cumpăr mâncare pentru micul dejun. Am încercat să o sun pe mama, să găsească o soluție, dar telefonul nu mergea pentru că nu plătisem factura. Am ezitat să spun cuiva, ca nu cumva să mă catalogheze în vreun fel sau să fiu un „caz caritabil”. Am fost atât de emoționată încât înainte de acele meciuri am vomitat și mi-a fost rău, știind că dacă voi pierde, cel mai probabil ăsta va fi sfârșitul carierei.

După ce am câștigat, am fost felicitată de antrenorii USTA, de organizatorii turneului, de fani, de toată lumea. M-am întrebat la acel moment, unde erau toți când eu plângeam și nimeni nu era în jurul meu să mă ajute.

Faptul că eram a cincea junioară din lume la acea vreme, dar eu nici nu-mi permiteam să mănânc micul dejun, a fost un apel de trezire și un punct de cotitură pentru mine. Toate astea m-au motivat să câștig, pentru ca într-o bună zi să joc liber și să nu-mi mai fac griji pentru nimic. Doar să joc sportul pe care-l iubesc. Depășirea acestor provocări mi-au arătat că nu există nimic ce nu pot face, atât pe teren cât și în afara lui.”

Ruan Roelofse, jucător clasat pe locul 160 în clasamentul de dublu:

„Acum aproximativ trei ani, când eram clasat pe 350 la simplu și jucam turnee futures, nu mai aveam mulți bani în cont și nu știam cum să fac să mă întorc acasă. Zborul către casă era în jur de 800 de dolari, astfel încât vă puteți închipui cam care erau banii pe care îi aveam eu în cont. Din fericire, câțiva oameni buni m-au ajutat, asta fiind singura mea opțiune.

Am încercat în mod constant să călătoresc cât de mult posibil, ceea ce înseamnă că am fost departe de casă între șase și opt luni. M-am întrebat mereu „ce fac eu?”. Mergeam la turnee săptămânal, făcând două sau trei sute de dolari. După impozitare nu mai rămâneam cu nimic. Am ajuns să mă întreb ce fac cu viața mea. Am 29 de ani acum. Nu am o diplomă, dar o voi obține. Alți oameni din jurul meu cu care am mers la școală au mașini, case și trăiesc o viață mai puțin stresantă. Ei mă văd și probabil se gândesc că trăiesc o viață luxoasă, jucând la Wimbledon. Dar în realitate eu abia pot supraviețui de la săptămână la săptămână. M-am gândit cum pot să mai câștig bani în timp ce călătoresc, dar nu mi-a venit nimic în minte până acum. Anul trecut a fost primul an în care am făcut 20.000 de dolari într-un an (am ajuns până pe locul 150 la dublu). Este puțin mai bine acum, dar încă nu e bine.

Madison Keys, jucătoare de top 10 în circuitul WTA:

„Când aveam 15 ani, am avut o tulburare de alimentație. Credeam că sunt oameni care, dacă mă văd la televizor, o să-mi spună că sunt grasă ori că trebuie să mai slăbesc câteva kilograme. Ulterior, asta mi-a intrat în cap. Am început să mănânc doar 100 de calorii pe zi. M-am luptat cu această problemă timp de doi ani, ceea ce a dus apoi la depresie. M-am închis complet. Nu am mai vorbit cu prietenii mei și cu mama. Am simți că îmi pun o mască, sperând ca nimeni să nu mă întrebe ce fac. Am devenit paranoică, pentru că am vrut să păstrez acest secret, astfel încât nimeni să nu mă întrebe și să nu-și facă griji. Asta până într-o zi când am realizat că ceea ce fac îmi afectează tenisul. Nu mă mai puteam antrena pentru că nu aveam nimic în corp. Am decis că trebuie să mă schimb și trebuie să mănânc. Mi-a luat ceva timp să mă deschid din nou către oameni. E ceva cu care încă mă lupt atunci când sunt stresată sau supărată, dar acum am o relație mult mai bună cu mâncarea”.

Nicole Gibbs, jucătoare de top 70 în circuitul WTA:

„Am suferit de depresie încă de la începutul adolescenței. În cele din urmă, mi-am împărtășit povestea într-un articol Telegraph la începutul anului, dar, până atunci, m-am luptat cu mine dacă să fac publică lupta mea de ani de zile. Îmi veneau în minte tot felul de întrebări și îndoieli care se rostogoleau în mintea mea: „De ce nu te-ai descurcat mai bine ? De ce nu ți-ai făcut jocul ? De ce nu ți-ai ținut mai bine nervii?” Și poate cea mai bântuitoare întrebare, când eram între primele 70 de jucătoare ale lumii: „cum e posibil să joci atât de mizerabil?”

Între timp, cu ajutorul meditației, medicamentelor și a unui stil de viață sănătos, lucrurile au mers bine și m-au ajutat mult. Cu toate astea, încă există sentimente de vinovăție și rușine pentru că „nu pot fi la fel de bună la tenis pe cât am fost la un moment dat„ sau sunt anxioasă la gândul cum va arăta viața mea după tenis.”

Katerina Stewart, 21 ani, jucătoare de Top 300 WTA

„Pe când aveam 12 ani mi-am dat seama că sunt gay. Am trăit mulți ani în confuzie, în negare, pretinzând că sunt altcineva decât cine eram, de fapt. Din nefericire, tenisul este un sport în care există multe prejudecăți, care îi face pe oameni să creadă că trebuie să-și formeze o imagine standard, să îndeplinească anumite standarde. Faptul că a trebuit să ascund atâta timp cine eram cu adevărat m-a făcut să alunec în depresie, iar anxietatea mi-a afectat jocul, pentru că-mi făceam mereu griji despre ce vor gândi oamenii despre mine, în loc să mă concentrez pe ce aveam de făcut pe teren. Mi-a fost atât de teamă să fiu eu cu adevărat, pentru că să fii gay nu era ușor acceptat, cu atât mai puțin în tenis. Mi-a luat ceva timp, iar în jur de 20 de ani am început să înțeleg că există o viață și în afara tenisului. După ce am reușit să depășesc teama de a fi judecat, sentimentul de a nu aparține, am putut să mă accept în sfârșit. Am găsit fericirea în mine, am redescoperit bucuria de a juca tenis și mi-am găsit și dragostea”.

IBAN RO51RNCB0079145659320001

Asociația Lideri în Mișcare,

Banca Comercială Română

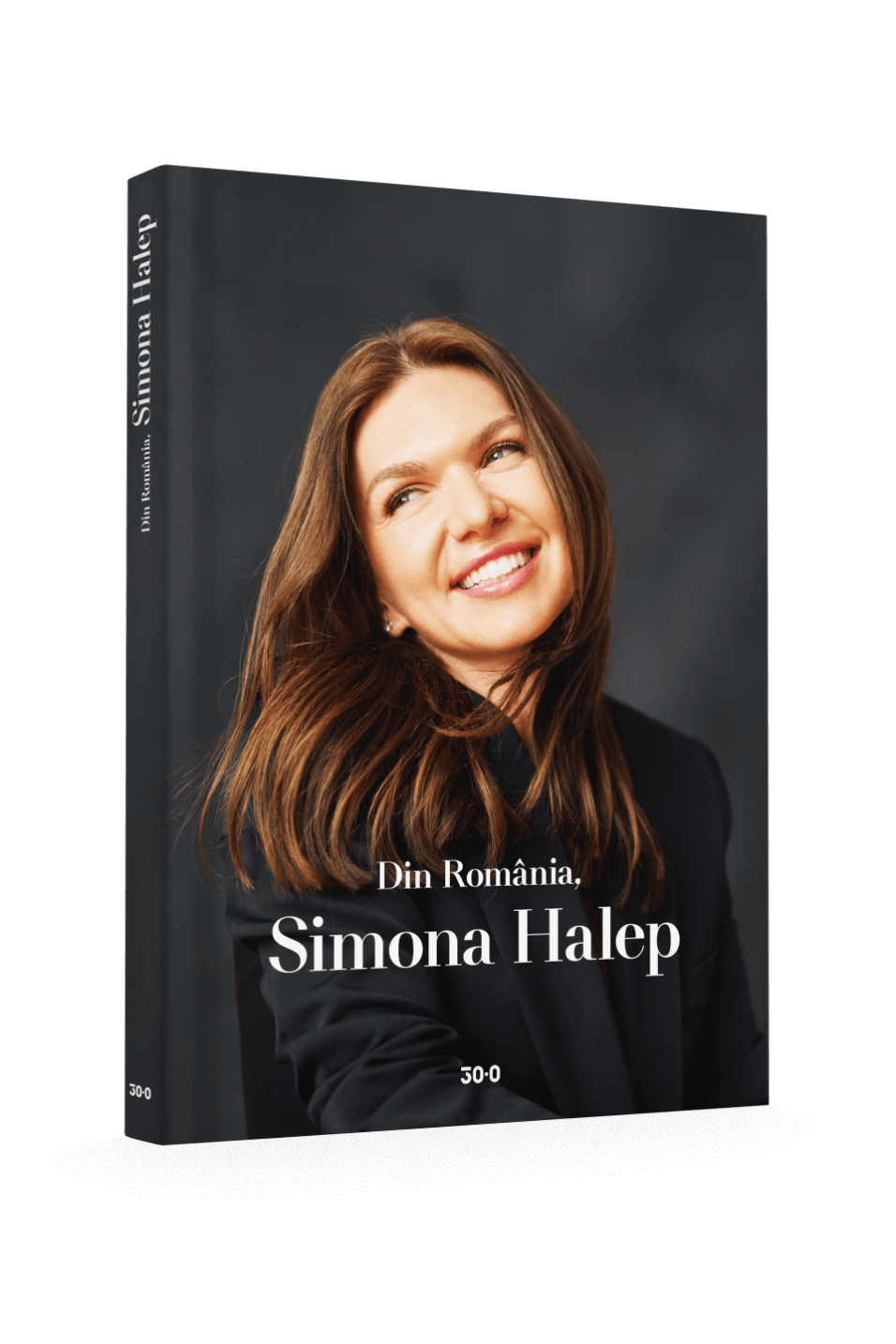

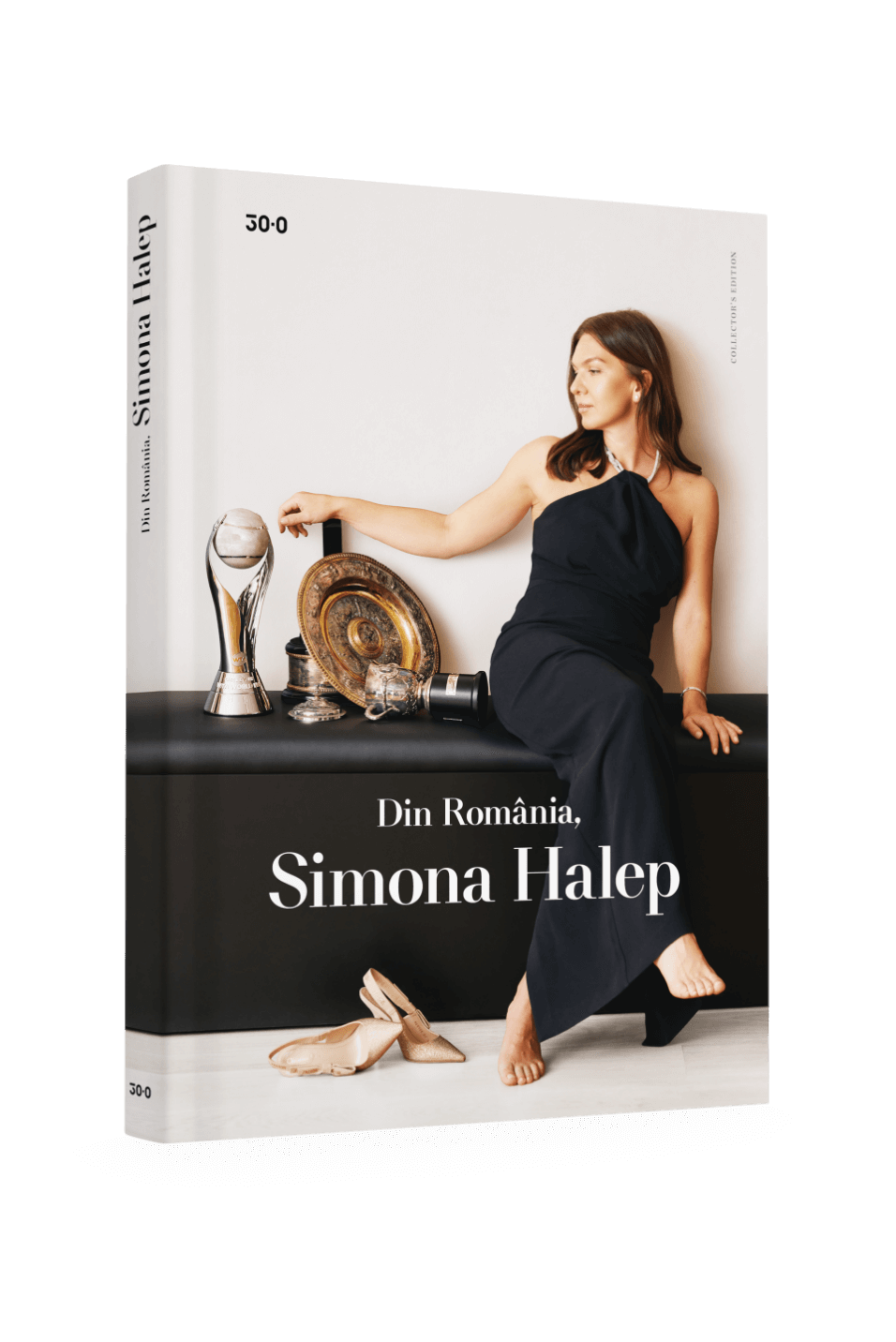

Din România, Simona Halep

S-a retras în acest an, dar ne-a lăsat cu amintiri și inspirație cât pentru o viață. Acum este timpul să o sărbătorim noi pe ea. 30-0 introduce “Din România, Simona Halep”, o biografie vizuală a carierei celei mai importante jucătoare de tenis din istoria României și una dintre cele mai mari legende ale sportului românesc.